Implementing JSON Schema in TypeScript: Type Inference, Test Automation, and RFC Standards

In recent years, various libraries for data validation in the TypeScript ecosystem have evolved with their own unique characteristics.

Notable examples include Zod which provides a declarative API, Ajv which faithfully follows the JSON Schema draft, and class-validator which supports Decorator-based validation.

JSON Schema can be utilized in various environments thanks to its flexible schema definition method and extensible structure. While reviewing several libraries, I was impressed by these advantages and wanted to explore them further.

I initially considered using Ajv but discovered limitations in type inference within the TypeScript environment. Eventually, I decided that the best way to deeply understand JSON Schema was to implement it myself.

Background

While Ajv is the most widely used library in the TypeScript ecosystem, it had the following type inference limitations:

import Ajv from 'ajv';

const ajv = new Ajv();

const validate = ajv.compile({

type: 'object',

// ❌ Even when starting to input here, it doesn't infer valid keywords for the 'object' type

});

const data = {

foo: 1,

bar: 'hello',

}

// ❌ Since validate() returns boolean, TypeScript cannot guarantee type safety

if (validate(data)) {

data.foo // ❌ Cannot access 'foo' property

}Of course, this issue can be resolved using Ajv Utility Types, but

The Ajv team provides utility types for TypeScript type definitions.

this creates a new problem of having to manage schema and type definitions separately. Ideally, I believed the schema definition itself should provide type information.

Approach

To solve these problems, I considered two approaches:

- Extending existing libraries to improve type inference capabilities

- Developing a new implementation optimized for type inference from scratch

After examining various possibilities, I chose to create a new implementation.

Building from scratch would allow me to fundamentally design the type system and help better understand how JSON Schema works. I also determined that it would enable me to provide a better developer experience.

Key Challenges

While developing the new library, I faced several technical challenges. In particular, I needed to solve the following tasks while improving JSON Schema’s type inference, building test automation, and reflecting RFC standards:

- Test Automation – How to systematically verify JSON Schema’s extensive test cases

- Format Keyword Implementation – Building an extensible format validation system while complying with RFC standards

- Type Inference Implementation – Designing a type system that accurately reflects JSON Schema’s complex structure

Let’s examine what problems we encountered and how we solved them one by one.

Test Automation

The JSON Schema team provides various JSON Schema test cases through their JSON-Schema-Test-Suite repository.

While these test cases were invaluable for verifying implementation correctness, we encountered several challenges in efficiently managing and executing them.

In particular, our goal was to automate testing and ensure consistent execution.

Initial Design Approach

Initially, we attempted to automate testing in the following way:

- Synchronize the repository to fetch the latest test cases

- Analyze directory structure and collect version-specific test files

- Generate type definitions for each test case using the TS Compiler API

- Write and execute automated test functions using the generated types

The TypeScript team provides an API that allows programmatic control of TypeScript compiler internals.

Implementation Process

First, we wrote CLI scripts and necessary utilities to automate repository synchronization.

This enabled us to quickly and reliably fetch the latest test cases into our local environment.

#!/usr/bin/env node

// Repository synchronization

await gitFetch({

org: "json-schema-org",

repo: "JSON-Schema-Test-Suite",

});

// Type definition generation

await writeTsFile(createInterface("Vocabulary", vocabulary));

await writeTsFile(createInterface("Alias", alias));

await writeTsFile(createType("Version", Object.keys(vocabulary)));Next, we designed the TestCaseManager class to easily manage test execution.

export class TestCaseManager<T extends keyof Vocabulary = keyof Vocabulary> {

constructor(public readonly version: T) {}

load = memoize(

async <K extends Vocabulary[T]>(

keyword: K,

options?: { skip?: string[] },

) => { ... },

);

}

// Instance for testing latest version

export const latestTestCase = new TestCaseManager("latest");After this preparation, we could automate JSON Schema validation in actual test code using TestCaseManager.

import { expect, test } from "vitest";

import { Schema } from "../../schema.js";

import {

TestCaseManager,

latestTestCase,

} from "../../utils/test-case-manager.js";

test.concurrent.for(await latestTestCase.load("additionalProperties"))(

TestCaseManager.format,

(testCase) => {

const schema = new Schema(testCase.schema);

expect(schema.validate(testCase.data)).toBe(testCase.expected);

},

);Problem Analysis and Improvements

While this approach initially seemed effective, we discovered several significant issues:

- Performance Issues – Dynamically reading all test files inevitably led to significantly slower execution times

- Maintenance Complexity – Paradoxically, we ended up spending more time maintaining the automation tools than using them

To address these issues, we developed a test file auto-generation CLI that reused existing tools.

However, after completing development, we discovered that the JSON Schema team already provided Bowtie, an official CLI testing tool.

It was a tool that effectively handled the problems we were trying to solve, but our tool development was already complete.

For future projects, we decided to more thoroughly research existing tools first.

The JSON Schema team uses Bowtie to verify implementation compatibility and automate testing. When an implementation passes the tests, it can display Reports and Badges on the website, making it easy for users to verify the library’s compliance with JSON Schema standards.

Format Keyword Implementation

JSON Schema’s Format keyword provides validation functionality based on various RFC standards. For example, it can validate specific string formats like date-time or uri.

I determined that this functionality was too broad in scope to be simply included in the same library.

Therefore, I decided to separate this functionality into a separate library and provide an interface similar to the familiar native JSON API and Date API.

import { FullTime } from "@imhonglu/format";

// Parse time string according to RFC standards

const time = FullTime.parse("15:59:60.123-08:00", {

year: 1998,

month: 12,

day: 31,

});

// Result:

// {

// hour: 15, // Hour

// minute: 59, // Minute

// second: 60, // Second (considering leap second)

// secfrac: ".123", // Fraction of second

// offset: { // Timezone offset

// sign: "-", // Sign

// hour: 8, // Hour

// minute: 0 // Minute

// }

// }

// Convert to standard format string

console.log(FullTime.stringify(time));

// '15:59:60.123-08:00'

// Support JSON serialization

console.log(JSON.stringify(time));

// '"15:59:60.123-08:00"'

// Automatic serialization within objects

console.log(

JSON.stringify({

name: "John",

createdAt: time, // FullTime instance automatically converts to string

})

)

// '{"name":"John","createdAt":"15:59:60.123-08:00"}'Designing Decorator for Serialization

First, we implemented Serializable Decorator to easily define frequently used Formatters.

Formatters refer to modules within the library that validate and process specific format strings like email addresses or URLs. Each format is implemented as an independent component.

import {

type Fn,

type SafeResult,

createSafeExecutor,

} from "@imhonglu/toolkit";

export function Serializable<

T extends Fn.Newable & {

parse: Fn.Callable<{ return: InstanceType<T> }>;

safeParse: Fn.Callable<{ return: SafeResult<InstanceType<T>> }>;

stringify: Fn.Callable<{ args: [InstanceType<T>]; return: string }>;

},

>(targetClass: T) { ... }There were two reasons for using Decorator:

First, it allows us to use Generic to make it behave like an Abstract Implement Class. As discussed in TypeScript’s related issue, constraints can be enforced through Decorator.

In TypeScript, there are limitations in mechanisms for enforcing abstract class implementation. Using Decorators can enforce required method implementation, complementing the limitations of abstract classes.

@Serializable

// ^^^^^^^^^^

// ❌ Compilation error occurs if `parse`, `stringify`, `safeParse`

// are not implemented due to Generic type constraints

class MyClass { }Second, when the first condition is met, it automatically implements certain methods (toString, toJSON, safeParse, etc.).

@Serializable

class MyClass {

public static parse() { ... }

public static stringify() { ... }

public static safeParse: SafeExecutor<typeof MyClass.parse>;

}

MyClass.safeParse(...); // ✅ Call automatically implemented `safeParse` methodUsing such Decorator allows us to ensure type safety while reducing repetitive code.

ABNF-based Regex Optimization

When converting ABNF grammar provided in RFC documents to regular expressions, we encountered issues with code reusability and debugging. This limitation was particularly evident in implementing uri from RFC 3986.

ABNF (Augmented Backus-Naur Form) is a grammar notation defined in RFC 5234, used as a standard for clearly describing protocols or formats.

For example, with regular expressions like this, it was very difficult to identify where problems occurred if certain characters were missing or updated:

const userinfo = /[a-zA-Z0-9\-._~!$&'()*+,;=:]+/;To solve this problem, we developed the @imhonglu/pattern-builder library applying the Builder Pattern. This allows us to convert ABNF grammar into more intuitive and maintainable code.

First, we define the most basic patterns:

import { characterSet, concat, hexDigit } from "@imhonglu/pattern-builder";

export const unreserved = characterSet(alpha, digit, /[\-._~]/);

export const pctEncoded = concat("%", hexDigit.clone().exact(2));

export const subDelims = characterSet(/[!$&'()*+,;=]/);These defined patterns can be combined to create more complex rules:

export const pchar = oneOf(

pctEncoded,

characterSet(unreserved, subDelims, /[:@]/),

);Finally, we complete the URI path pattern:

const slash = characterSet("/").optional();

const path = concat(

concat(slash, pchar.clone().nonCapturingGroup().oneOrMore())

.nonCapturingGroup()

.zeroOrMore(),

// Optional trailing slash

slash,

)

.anchor()

.toRegExp();Thanks to this step-by-step pattern definition approach:

- We can more clearly express the intent and role of ABNF rules

- Each pattern can be independently modified and reused

- We can test and debug specific parts separately

This pattern builder approach significantly improved code readability and maintainability, becoming an important foundation for implementing core functionality in the @imhonglu/format library.

Type Inference Implementation

Through the Format keyword implementation and test automation discussed earlier, we laid the foundation for the library. However, the most important aspect in a TypeScript environment is type safety.

Implementing effective type inference for JSON Schema was the final challenge to achieve this.

Rather than simply inferring based on the type keyword, we needed an extensible type system that reflects the structural characteristics of the schema.

Structuring the Type System

First, we defined the type keyword as a Discriminated Union to narrow down possible types in advance.

This allowed us to utilize TypeScript’s type analysis capabilities for automatic type inference. (Control Flow Analysis)

Discriminated Union and Control Flow Analysis are useful concepts for type inference. For detailed explanations and examples, see Discriminated Unions and Control Flow Analysis Example.

However, JSON Schema is not defined by simple type properties alone.

There are various keywords for validation, and we needed to manage them systematically.

Therefore, we adopted an approach of separating major keywords used in JSON Schema into reusable interfaces, clearly defining necessary properties for each type.

We organized these into six categories based on documentation:

BasicMetaData- Metadata properties liketitle,description,defaultStructuralValidation- Properties for structural validation of numbers, strings, arrays, etc.StringEncodedData- String data-related properties likecontentEncoding,contentMediaTypeFormat- Format validation likedate-time,email,uriApplyingSubSchema- Sub-schema related properties like$ref,allOf,oneOf,anyOfUnevaluatedLocations- Additional property definitions likeunevaluatedProperties,unevaluatedItems

Let’s look at StructuralValidation as an example:

export namespace StructuralValidation {

/**

* @see {@link https://json-schema.org/draft/2020-12/draft-bhutton-json-schema-validation-01#section-6.2 | Numeric}

*/

export interface Numeric {

multipleOf?: number;

maximum?: number;

exclusiveMaximum?: number;

minimum?: number;

exclusiveMinimum?: number;

}

/**

* @see {@link https://json-schema.org/draft/2020-12/draft-bhutton-json-schema-validation-01#section-6.3 | String}

*/

export interface String {

maxLength?: number;

minLength?: number;

pattern?: string;

}

// ... omittedBy separating each property into independent interfaces, we can compose desired schema types by combining only necessary properties.

Defining JSON Schema Types

Based on the separated structure above, we can define the top-level JSON Schema type:

/**

* @see {@link https://json-schema.org/draft/2020-12/draft-bhutton-json-schema-01#section-4.3.1 | ObjectSchema}

*/

export interface ObjectSchema

extends Core<JsonSchema>,

BasicMetaData,

StructuralValidation.All,

StringEncodedData<JsonSchema>,

Format,

ApplyingSubSchema.All<JsonSchema>,

UnevaluatedLocations.All<JsonSchema> {}

/**

* @see {@link https://json-schema.org/draft/2020-12/draft-bhutton-json-schema-01#section-4.3.2 | BooleanSchema}

*/

export type BooleanSchema = boolean;

export type JsonSchema = ObjectSchema | BooleanSchema;BooleanSchema is different from the

type: "boolean"property.trueallows all values andfalserejects all values, acting as a simple schema that only validates the existence of data.

Now we can integrate the core type structure of JSON Schema into one.

And by extending this, we can define more specific types:

export namespace SchemaDefinition {

// ... omitted

export interface NumericType

extends Core<Type>,

BasicMetaData,

Pick<StructuralValidation.Any, "type">,

StructuralValidation.Numeric {

type: "number" | "integer";

}

export type Type =

| BooleanSchema

| ConstType

| EnumType

| NullType

| BooleanType

| ObjectType

| ArrayType

| StringType

| NumericType

| Schema;

}Applying Type Inference

By applying the types defined above as Generic to the Schema class, we could statically infer the structure of JSON Schema:

export class Schema<T extends SchemaDefinition.Type = SchemaDefinition.Type> {

constructor(public schema: T) {}

// ... omitted

}// Schema instance creation example

const schema = new Schema({

type: "object",

// ✅ TypeScript automatically infers allowed keywords for 'object' type

// e.g., properties, required, additionalProperties, etc.

properties: {

name: {

type: "string",

// ✅ TypeScript automatically infers allowed keywords for 'string' type

// e.g., maxLength, minLength, pattern, etc.

maxLength: 10,

},

},

});This allows us to actively utilize TypeScript’s type checking when defining schemas to reduce developer mistakes and perform safe data validation.

Introduction

Let’s look at how the library we developed while solving these various challenges actually works.

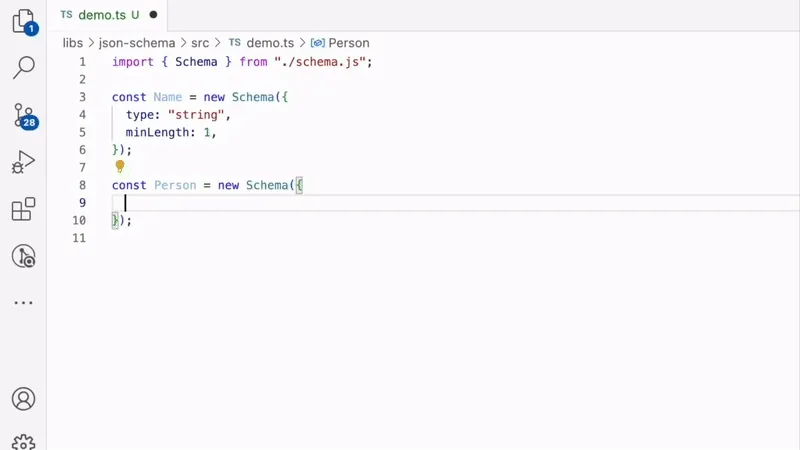

The demo below shows how type inference works:

Features

- Complies with JSON Schema 2020-12 Draft specification

- Statically infers appropriate keywords when defining schemas

- Statically infers types of determined schemas

- Supports recursive type inference for nested

Schema Instance - Enables type inference based on

requiredkeyword - Provides

parseandstringifymethods for easy schema conversion and utilization - Verified based on JSON-Schema-test-suite

Test automation using JSON-Schema-test-suite and implementing format keywords based on RFC specifications took longer than expected.

Although the development period was longer than planned, the experience gained in this process became an opportunity to further enhance the project’s completeness.

Future Plans

While basic functionality is implemented, there’s still room for improvement. We plan to focus on developing the following areas:

- Custom Features

- Customizing validation messages

- Custom error handling

- Improving Developer Experience

- Providing more detailed error messages and debugging information

- Improving documentation

- Performance Optimization

- Optimizing schema compilation process

- Improving memory usage

Contributing

This project is still evolving and welcomes community feedback and contributions. If you’re interested, please visit our repository.

Your opinions and suggestions will be the driving force in further developing this library. Thank you!